A very basic primer on behavioral economics

Behavioral Economics is a science combining economics and psychology to observe and understand human behavior and decision-making processes. Behavioral economics recognizes that people often do not have sufficient time, data or resources while making decisions. This can prevent us from optimally evaluating every decision i.e. being perfectly rational. To deal with our limitations, people devise shortcuts or heuristics to aid in decision-making. These shortcuts can often lead to non-ideal choices, but interestingly tend to be predictably irrational.

A lot of people would credit Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman for inventing the field of behavioral economics. In their seminal 1974 paper titled Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases and in a series of following articles, Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated the ways in which human beings consistently erred when forced to make decisions in the face of uncertainty. As Michael Lewis writes in his recent book, The Undoing Project, “Their work created the field of behavioral economics, revolutionized Big Data studies, advanced evidence-based medicine, led to a new approach to government regulation, and made much of my own work possible. Kahneman and Tversky are more responsible than anybody for the powerful trend to mistrust human intuition and defer to algorithms”.

The field has continued to evolve since then with leadings lights such as Richard Thaler, Daniel Ariely, George Loewenstein and in the field of healh care, Dr. David Asch and Dr. Kevin Volpp and more recently Katherine Milkman and Angela Duckworth.

How are traditional economics and behavioral economics different?

To say that traditional economists (the so-called Chicago School of economists) and behavioral economists agree with each other fully would be a gross misstatement. As an example, after hearing that Richard Thaler won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017, Paul Krugman, the 2008 winner tweeted “Yes! Behavioral econ is the best thing to happen to the field in generations, and Thaler showed the way”. Other reactions while supportive were not as enthusiastic. Here’s an extract the Wikipedia page on Thaler, “However, Thaler’s selection was not met with universal acclaim; Robert Shiller (one of the 2013 laureates) noted that some economists still view Thaler’s incorporation of a psychological perspective within an economics framework as a dubious proposition. And, an article in The Economist simultaneously praised Thaler and his fellow behavioral colleagues while bemoaning the practical difficulties that have resulted from causing “economists as a whole to back away a bit from grand theorizing, and to focus more on empirical work and specific policy questions.”” The cause of these disagreements seems to stem either from the core assumptions underlying each field, as well as from the methods each discipline employs.

Experimental economists traditionally believed that human beings were rational human beings i.e. belong to the species homo economicus. Behavioral economists contend that that is not always the case. To paraphrase a quote from the book, Advances in Behavioral Economics, behavioral economists define themselves on the application of psychological insights to economics and not necessarily on the research methods that they employ. Experimental economists, on the other hand, define themselves on the exclusive use of experimentation as a research tool and also seem to have a virtual prohibition against deceiving test subjects.

Secondly, since experimental economists are focused on broadly applicable theories, they often tend to not include data such as demographics, self-reported data, context etc. which behavioral economists use constantly. For example, if you consistently vote Republican, your view on tax reductions is likely very different from someone who leans Democratic. Real life, demographics and personal biases do matter when decisions are being made.

Thirdly, economics experiments try to weed out biases. So tasks are repeated again and again until some consistency of response is achieved. It is this latter set of data that is often used for analysis. While this equilibrium response is useful, behavioral economists contend that since most of the major decisions we make in life - marriage, healthy behaviors, educational decisions, saving for retirement, buying homes or cars - happen just a few times in a person’s life, the first few iterations of an experiment are equally valuable.

These are just some of the differences between these two schools of research and hopefully, a grand unified theory is around the corner.

Some health care context

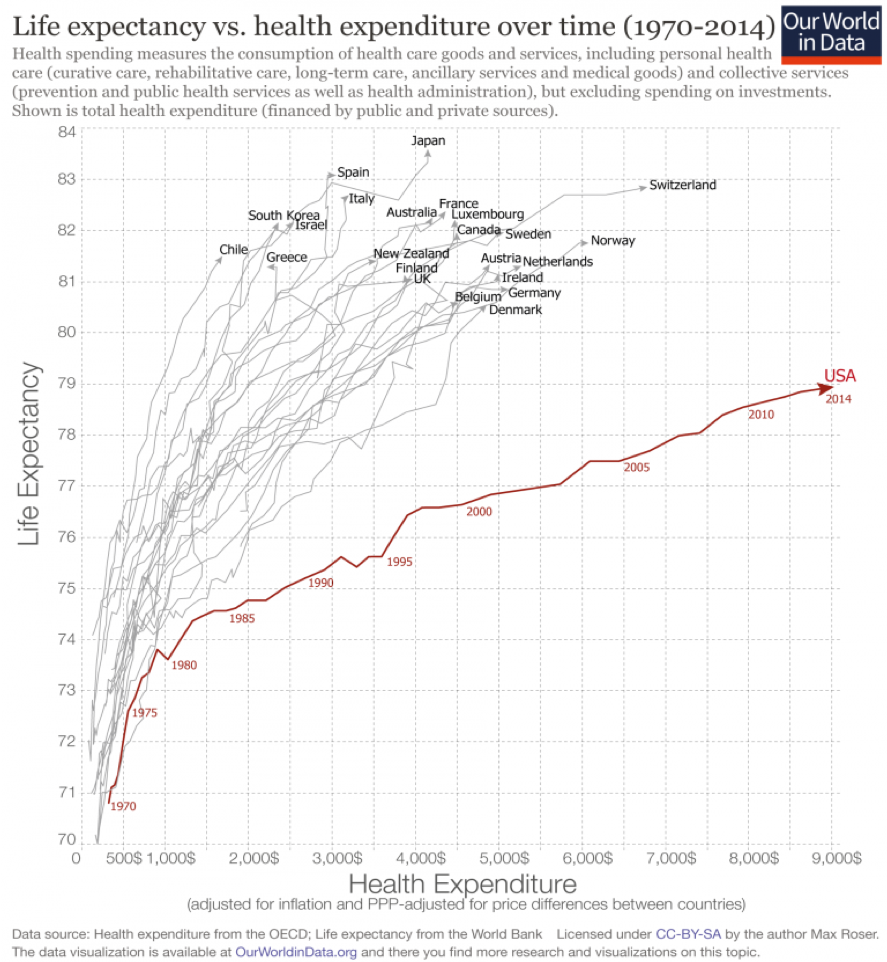

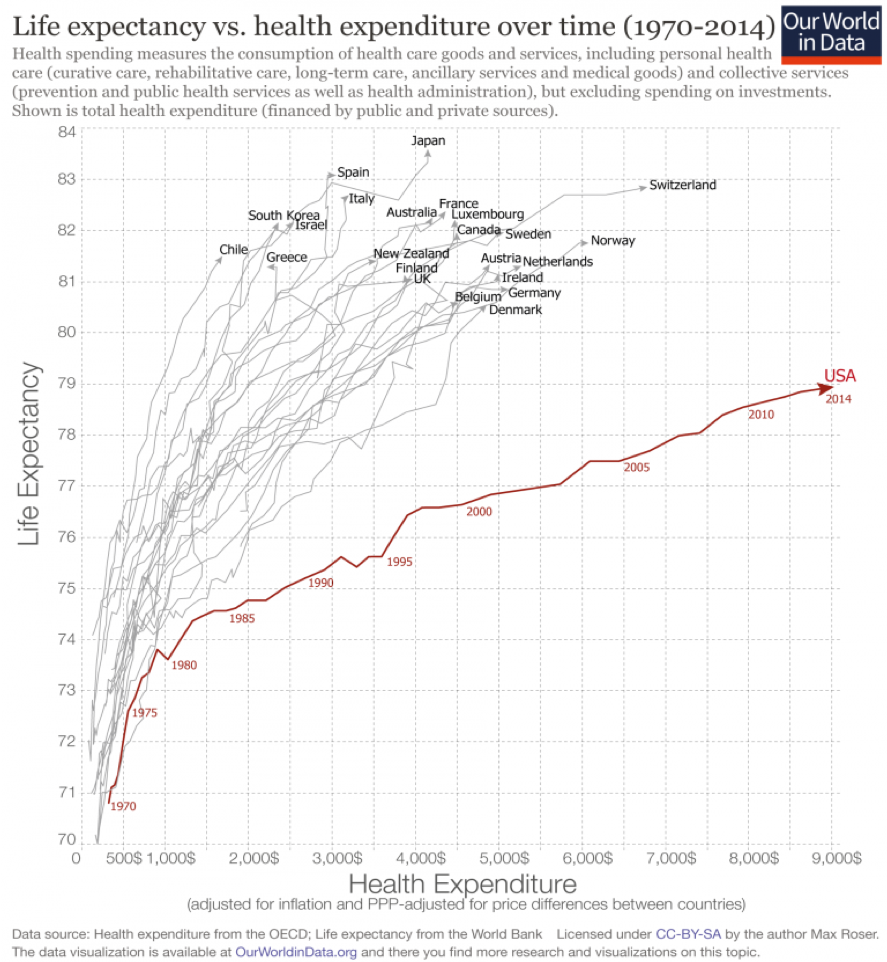

Let’s look at why behavioral economics in health care is so promising. We’ve all seen various variants of this chart showing the poor performance of the United States in terms of life expectancy given our expenditure on health care. Additionally, if you look at the data on the various causes of premature mortality in the US, about 40% can be attributed to poor behavioral patterns. One could easily interpret this to say that health care is a behavioral change change business. It is in this context that we will delve into further details of the application of behavioral economics to improving / changing health care behavior. In general, the approach will be to look at the “errors” people make that consistently deviate from rational behavior and present ways in which researchers and implementers are trying to overcome these issues.

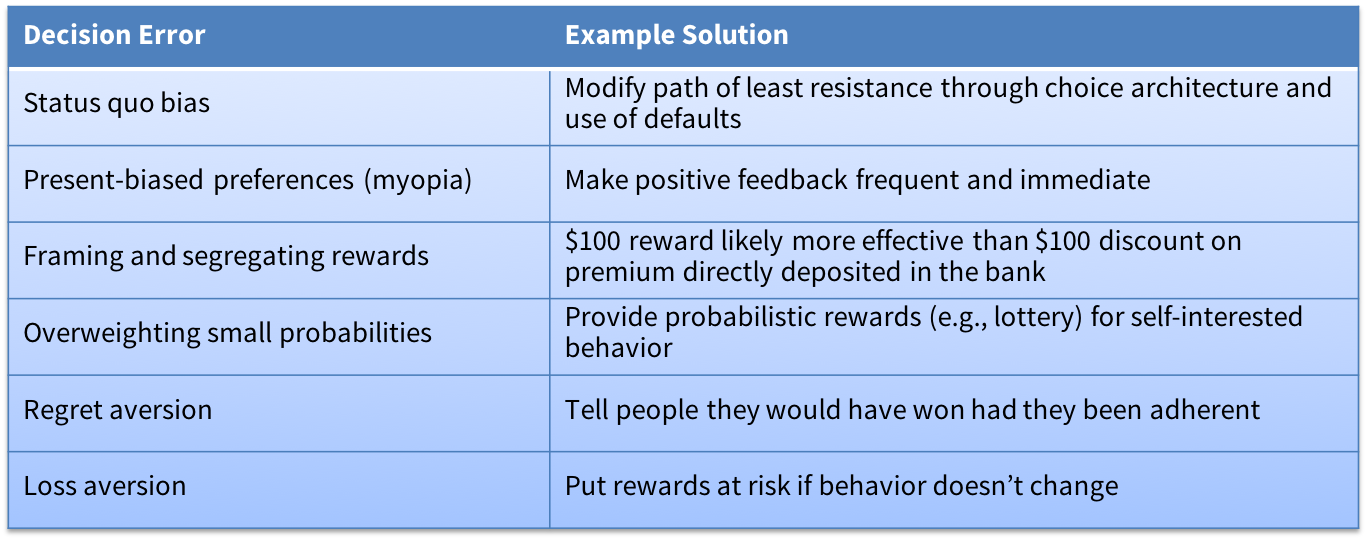

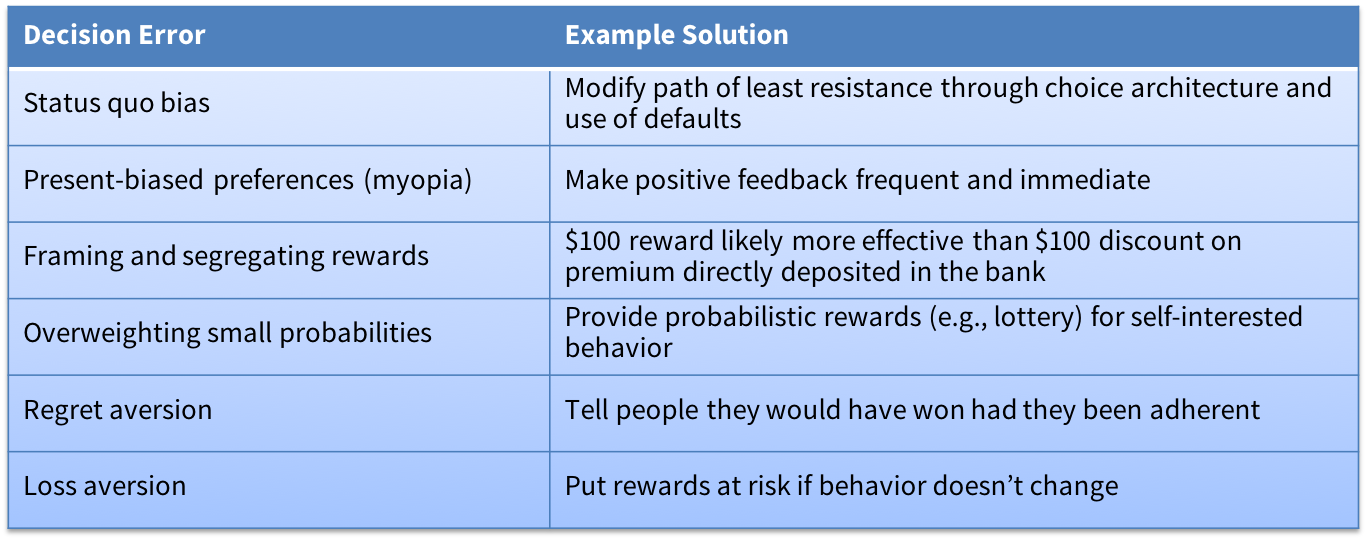

The key such errors in decision making are as follows:

Source: Loewenstein, G., Brennan, T. and Volpp, K. (2007). Protecting People from Themselves: Using Decision Errors to Help People Improve Their Health. JAMA. 298(20), 2415-2417; Volpp, Pauly, Loewenstein, Bangsberg, (2009) Pay for Performance for Patients. Health Affairs 28(1): 206-14.

In the next article, we’ll use a few examples to illustrate each of these core concepts and theories behind behavioral economics. We will also explore some of the policy changes and other interesting experiments leveraging behavioral economics that have been implemented in the real world and the associated outcomes. We’ll be doing this as much as possible in the health care context.